Last Updated on 07/05/2022 by Mario A. Rosato

Re-publication of an article by Mario A. Rosé on Agronotizie

Bureaucracy and Nimby at Italian levels, but perhaps with clearer regulations.

The political debate of the last month has focused on the consequences for the Italian economy of the international embargo on Russian gas. Despite the Guidelines contained in the communication of the Ce REPowerEU and the Spanish example of a quick and pragmatic reaction to the supply problem, the only answer that Italian politics was able to find was simply to replace dependence on Russia with dependence on other countries. Inter alia, not all democratic or politically stable.

Read also

Biogas and independence from Russian gas: Spain will beat Italy on time?

According to the president of the Italian Biogas Consortium (Cib), Piero Gattoni, to increase by 20% the production of existing biogas plants would be enough only to reduce the bureaucratic burden. Moreover, says Gattoni, the delay in issuing clearer rules on the injection of biomethane into the network has slowed the construction of new plants, which today would be able to replace the 30% of natural gas imports. A delay what time the Government tries to compensate by desperately seeking alternatives abroad.

Meanwhile, the Parliament Italian perseveres in Byzantine discussions on the possibility of reintroducing nuclear power or install more solar panels on the roofs to solve the energy crisis, a small English village has reached the paradigm of’circular economy and l’energy self-sufficiency. South Molton is a rural village with 4.093 inhabitants located in Devon, about 300 miles west of London. L’Condate biogas plant (Opening photo of the article), placed at approx 1,5 kilometers from the town center, produces enough renewable electricity for 2.300 families, and gas for 4.600.

It is one of several plants belonging to the Ixora Energy Group. It is equipped with two cogenerators from 500 kW and an upgrading system with capacities up to 600 m3/h. It looks a lot like any of the over a thousand existing plants in Italy, except for two details: the design choice to install two cogenerators in parallel instead of the usual engine from 1 MW, and the simultaneous production of electricity and biomethane, still a rarity in our country due to unclear regulations.

Thanks to the general manager, Mr Darren Stockley, who kindly gave us his time to answer our questions, we offer our readers a summary on the general state of simultaneous electricity and biomethane production in the UK.

Years ago, in Italy it was allowed to feed the digesters with up to 100% of dedicated crops, and many old plants still operate on this diet. After the revision of the Red II, the limit for new plants has been set at 30% of the total weight in feed. Since the UK is no longer subject to the EU regulations, what are the percentages of dedicated crops and residues / by-products in your feed mixture?

“New plants in the UK must be powered with at least 50% of agricultural residues. Our plants are not subject to this rule, so we can operate with mixtures containing the 20-50% of agricultural residues. Condate works with the 20% of agricultural residues. We are constantly trying to identify new sources of agricultural residues to increase their percentage in the feed mix”.

In your web page it says that Ixora Energy pays local farmers for their manure and by-products. Calculate the price based on measurements of the Bmp of each lot? Or take the German approach, based on Bmp tables?

“We pay farmers based on the content of Ss, Dry substance, of their supplies. We have contracts for the entire life of the plant (15 years) and the price per ton of dry matter is updated every year by an independent expert who reviews their costs”.

Return the digestate to the farmers free of charge or make them pay for it as fertilizer?

“We give it to him for free backards, but we do not allow them to charge us with artificial fertilizer costs in the by-products we buy”.

How do you manage digestate?

“We separate the solid and liquid fractions. The solid is applied directly to the ground. The liquid fraction is currently used as a liquid fertilizer, but we are working with several British and European companies to extract and recycle water. This is an area for which we are very interested in finding a solution”.

Recover the residual heat from the cogenerator and / or the CO2 from the upgrading system for some use?

“The heat is recovered, but only to reduce the humidity of the digestate. We are evaluating several options to make the best use of heat for hydroponic and vertical farming. We are also modifying our plants to capture CO2 for its use in the food industry”.

You have designed the Condate plant from the beginning for the simultaneous production of electricity and biomethane? Or you started as an electrical system and then added biomethane production at a later time?

“It was designed from the outset for the production of electricity and gas. Gas production is limited only by the extent of the pipeline serving our community”.

What are the electrical and biomethane rated powers?

“The flow rate of biomethane to the pipeline is approx 500 m3/h, and the electric power is 1 MW (of which 400 kW represent the self-consumption of the system)”.

The production of electricity and gas are simultaneous, or the electric generator is switched off when biomethane is produced?

“Before, enough electricity is produced to power the plant, then gas production is maximized, then the electric one. Therefore, the production is simultaneous“.

How much time did you waste for the bureaucratic procedures before getting permission to start construction and operation?

“They have passed 12-18 months to obtain the building and environmental permits needed to start construction. Lately this problem has gotten worse in the UK, despite the need to become energy self-sufficient”.

There were local protest committees, or spreading fake news on biogas in an attempt to block your project? How did you solve the problem?

“Condate was not a problem, but we have other plants that suffer from the protests of the neighbors. This situation has worsened with the use of social networks. To overcome this problem, we try to invite as many people as possible to visit the site and show them that the rumors about biogas plants are incorrect. We also try to dialogue with local politicians to show the benefits that the plant provides to the environment”.

How the sale of electricity and gas is organized in England? Sell gas and electricity directly to the municipality or to a distributor that owns a local network? Or inject them into the national grid?

“We directly inject gas and electricity into national networks. We sell the production to private energy companies such as BP / Total / EDF, which they resell to the final consumer”.

British regulations recognize a rewarded rate compared to market prices, or subsidize the construction of the plant, or recognize only a fixed proportional to the nominal power of the system?

“We receive a subsidized payment based on actual gas and electricity production. Payment is made monthly by the Government and we must demonstrate our environmental performance by providing detailed information. Everything is regularly checked”.

summing up: the situation in England does not seem so different from the Italian one. Over-regulation seems to be a recurring problem both inside and outside the EU.

England benefits from greater flexibility in the use of dedicated crops to feed the digesters and slightly shorter administrative times, though 12-18 months is not a very short time if we consider the urgency of global climate change. The anaerobic digestion technology of the Condate plant is Central European, as in the majority of Italian plants. The logic of state incentives on biomethane and electricity products, as well as the way these incentives are administered, they look similar in both countries.

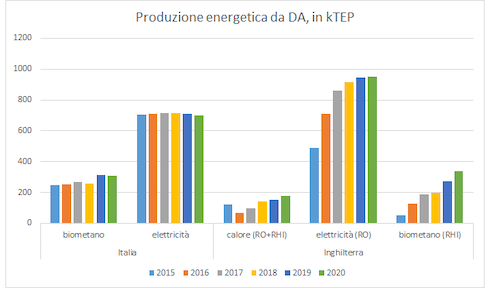

Comparing the statistics of energy production from biogas on a national scale, we observe some interesting additional differences on the evolution of both markets (Photo 1).

Photo 1: Official data on English production. Official data on Italian production. Conversion factors to be able to compare data from different sources: 1 TJ = 23,8846 TEP e 1 GWh = 85,9845 TEP

(Click on the image to enlarge)

On reason for which the biogas industry is growing faster in the UK than in Italy it seems to be legislation.

In Italy, the biogas boom began years earlier than in England, but Italian policies have remained static and at times alternately contradictory, therefore the Italian anaerobic digestion market is still strong globally, but stagnant. In the United Kingdom, the sector expanded between 2009 and the 2017 under the legislation known as Renewables Obligation (RO), main incentive mechanism for large renewable energy projects. In March 2017 RO is over and most of the significant growth in energy produced by anaerobic digestion is attributed to various mechanisms, specially designed to provide sufficient financial incentives to reduce the cost gap between conventional and renewable energy sources.

A example of these is the non-domestic Renewable Heat Incentive (Rhi, incentive for the production of heat for non-domestic use), which provides payments to encourage the production of renewable heat, both through direct production (combustion of biogas on site) and injection of biomethane into the network. In Italy, there is no direct combustion support policy for the production of heat from biogas. Incentives for heat recovery from cogenerators are not attractive to investors and plants capable of producing electricity and biomethane are just a handful.

Then, we deduce that the culprits of the stagnation of the biogas industry in Italy are bureaucracy and short-sighted policies. Elementary, Watson!